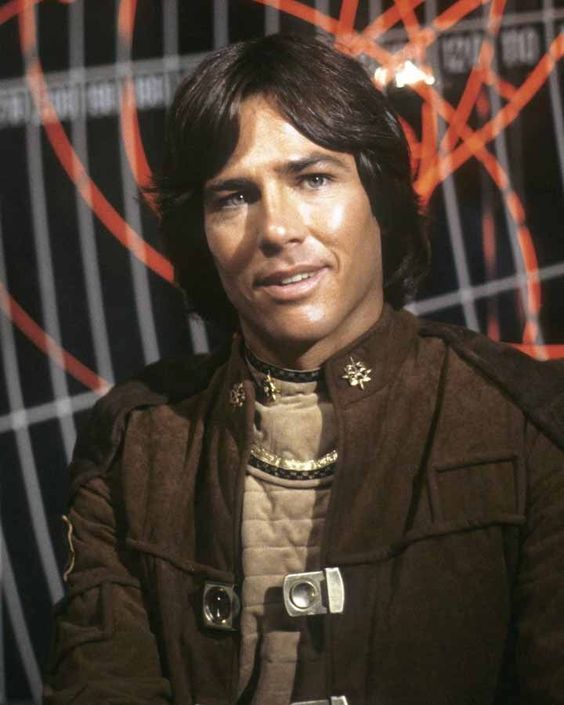

I’ve was saddened last weekend to learn of the passing of Glen A. Larson, the writer and producer behind many of the television series that occupied real estate in my imagination as I was growing up in the 1970s and ’80s, shows such as The Six Million Dollar Man, Quincy, M.E. (the original forensic police procedural!), The Hardy Boys/Nancy Drew Mysteries, Buck Rogers in the 25th Century, Knight Rider, The Fall Guy, and of course Magnum, P.I. I even have a soft spot for several of his lesser efforts: B.J. and the Bear, Manimal, Automan, and Cover Up, which I remember as a pretty terrific series that was derailed by the heartbreaking and utterly pointless death of its costar, a hunky young actor with a bright future named Jon-Erik Hexum. (Incidentally, why isn’t that show on DVD? Surely I’m not the only one who remembers it with some fondness? Or for that matter, how about the TV movie-of-the-week Hexum made with Joan Collins, The Making of a Male Model? Surely that’s got a big enough cult following to warrant a manufacture-on-demand disc?)

I’ve was saddened last weekend to learn of the passing of Glen A. Larson, the writer and producer behind many of the television series that occupied real estate in my imagination as I was growing up in the 1970s and ’80s, shows such as The Six Million Dollar Man, Quincy, M.E. (the original forensic police procedural!), The Hardy Boys/Nancy Drew Mysteries, Buck Rogers in the 25th Century, Knight Rider, The Fall Guy, and of course Magnum, P.I. I even have a soft spot for several of his lesser efforts: B.J. and the Bear, Manimal, Automan, and Cover Up, which I remember as a pretty terrific series that was derailed by the heartbreaking and utterly pointless death of its costar, a hunky young actor with a bright future named Jon-Erik Hexum. (Incidentally, why isn’t that show on DVD? Surely I’m not the only one who remembers it with some fondness? Or for that matter, how about the TV movie-of-the-week Hexum made with Joan Collins, The Making of a Male Model? Surely that’s got a big enough cult following to warrant a manufacture-on-demand disc?)

Without question, though, the Glen Larson production that made the biggest impression on me was his epic space-opera Battlestar Galactica. Premiering in September 1978, a little over a year after Star Wars took the world by storm, Galactica was widely dismissed by critics as a rip-off of a hit movie. In fact, 20th Century Fox actually sued Larson and Universal Studios for plagiarism, because they apparently believed George Lucas had a monopoly on space-based stories featuring robots, dogfighting fighter craft launched from gigantic warships, ray-gun shootouts with armor-clad villains, and planetary-scale holocausts. Never mind that these were all common genre tropes stretching back to the pulp magazines of the 1920s, or that Lucas himself had borrowed heavily from Frank Herbert’s Dune. And never mind as well that Larson had been shopping around the core concept that became Galactica — originally titled Adam’s Ark — since the late 1960s. The suit was eventually settled, but Larson never overcame his reputation as a hack (the notoriously testy science-fiction author Harlan Ellison once called him “Glen Larceny”). Several of his later shows didn’t help matters: Automan was very obviously inspired by Tron, and Manimal tried to cash in on the “bubbling face” transformation effects seen in An American Werewolf in London and The Howling. But I’ve always thought the term “rip-off” was overly harsh, and especially unfair in the case of Galactica. Even to a nine-year-old boy, it was pretty obvious that Galactica was inspired less by Star Wars than by various far-out ideas that were swirling around in the cultural consciousness of the ’70s — pseudoscientific woo-woo stuff like Atlantis and the “ancient astronauts” described in von Daniken’s Chariots of the Gods, and the craze for all things Egyptian in the wake of the touring King Tut exhibitions — as well as by Larson’s own Mormon beliefs.

Yes, what you’ve heard all these years is true: Glen A. Larson was a Mormon, and many of the underpinnings of Battlestar Galactica can be traced to LDS folklore, if not actual scripture. The Tribes of Man, the Lost 13th Tribe, the planet Kobol as the birthplace of humanity (actually Kolob, in Mormon cosmology), referring to a wedding ceremony as a “sealing” and the civilian leadership as the Quorum (or, in some episodes, the Council) of the Twelve… that’s all straight out of Mormonism. And if those elements aren’t big enough clues to Larson’s inspiration, consider the mysterious Beings of Light seen in some of the show’s later episodes. These ethereal creatures take a benevolent interest in the Galactica and her fleet of refugees, and memorably tell our heroes “As you are now, we once were; as we are now, you may become,” suggesting they evolved from flesh-and-blood humanlike bodies into some kind of higher form. That’s the Mormon conception of angels in a nutshell.

I remember talking with my friends in elementary school about this stuff while Battlestar was originally airing. At the time, and for many years after, I really didn’t want to accept the connection between the church and one of my favorite TV shows. I don’t know if it still goes on much, but there was a time when Mormons were constantly claiming (often incorrectly) that one celebrity or another was a member of the church, as a way of demonstrating that Mormons were cool, too, I suppose, and pointing out elements of Battlestar borrowed from Mormonism always struck me as an extension of that. But of course I was wrong, and in later years as I became a more educated and sophisticated viewer, I could no longer deny the obvious. And honestly, I’ve now decided as an adult that the show’s Mormon roots might actually be part of its appeal for me. I never officially became a member of the LDS faith myself, but I grew up immersed in it — believe it or not, I did occasionally attend services as a child, and I’ve always been surrounded by family and friends who are members — so all of those elements are familiar to me, and even comforting, in a way. Battlestar Galactica, on some fundamental level, simply feels like home to me. That’s why I can overlook its many flaws, and I suspect that’s also is a big part of why I just couldn’t get on board with Ron Moore’s remake a few years ago. Well, that plus the fact that I tend to dislike remakes on general principle. But the Battlestar “reimagining” or whatever Moore called it really rubbed me wrong right from the get-go, and the best explanation I can offer for that is that the old series felt like home, and the new one… just didn’t.

The other big reason I didn’t care for the remake was because I feel that Moore missed (or deliberately abandoned) the core concept that really lay at the heart of the original. Beneath all the special effects and the space-opera explosions and pyramid-power nonsense, Battlestar Galactica was about family. The three main characters — Commander Adama, played by Lorne Greene, his son Captain Apollo, and Apollo’s best friend, the maverick Lt. Starbuck — comprised a solid and loving family unit. (Adama also had a daughter, Athena, played by the lovely Maren Jensen, but she faded from prominence during the show’s run and had entirely disappeared by time it ended; I’ve never heard an explanation for why.) You always knew that no matter how bad things got for the fleet, no matter what disasters befell our heroes, they had that relationship — a metaphorical pyramid, to continue the Egyptian motif — to rely upon. In Ron Moore’s Galactica, by contrast, every single relationship was completely dysfunctional. Not only could the reimagined Adama, Apollo, and Starbuck not rely on each other, they didn’t even like each other, at least in the early episodes of the show I saw. And that really bothered me. I got the point Moore was making — his thematic preoccupation was less about ancient astronauts than the paranoia engendered by 9/11, the notion that you literally can’t trust anybody — but I didn’t like it. That’s not how I view the world, or at least not how I want to to view it.

But getting back to Larson’s original, there’s a funny thing about that comforting sense of family the show generated: I’ve found it extends into the real world as well. When I attended the first Salt Lake Comic Con a year ago, the celebrity guests I was most pleased to meet turned out not to be the star attractions — William Shatner and the legendary comic-book creator Stan Lee — but rather three cast members from Glen Larson’s Battlestar Galactica: Richard Hatch (Apollo), Dirk Benedict (Starbuck), and Noah Hathaway (Boxey). I’ve found that I’m relatively composed in meeting celebs, but these three, in particular, were easy for me to talk to. I won’t say it was like I’ve known them my whole life, because that sounds a little too creepy-stalkerish, but that’s not an entirely inaccurate way of describing it. Meeting these guys was like… being introduced to far-flung cousins. You don’t actually know them, but you nevertheless feel a sense of connection with them. They were like family, in other words. And I’m not being hyperbolic when I say that I cherished the few moments I spent chatting with them. I owe Glen Larson for that experience, and for the hours and hours of enjoyment, escape, inspiration, and yes, comfort that his work has brought me over the last 35 years.

And so, Glen, wherever you may be tonight, I raise a goblet of thousand-yahren-old ambrosia to you. I hope those Beings of Light were waiting for you in the end…