“In these eights days of the Apollo 11 mission, the world was witness to not only the triumph of technology, but to the strength of Man’s resolve and the persistence of his imagination. Through all times, the moon has endured out there, pale and distant, determining the tides and tugging at the heart, a symbol, a beacon, a goal. Now, Man has prevailed. He’s landed on the moon; he’s stabbed into its crust; he’s stolen some of its soil to bring back in a tiny treasure ship to perhaps unlock some of its secrets.

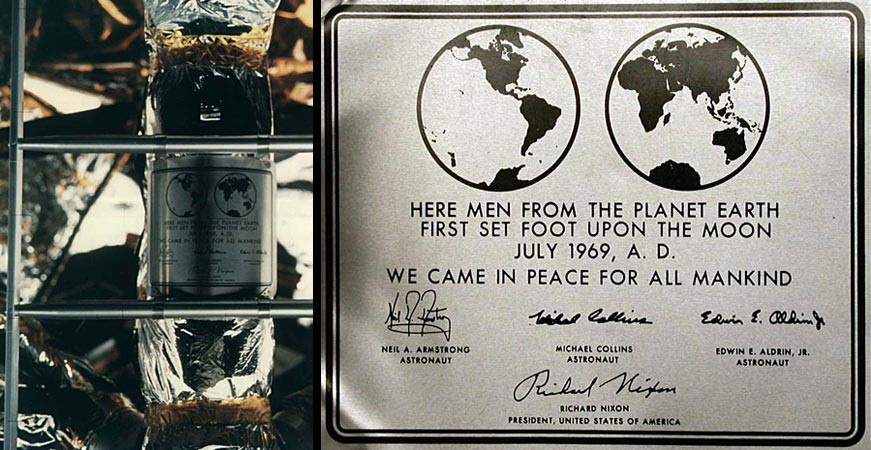

“The date’s now indelible. It’s going to be remembered as long as Man survives—July 20,1969—the day a man reached and walked on the moon. The least of us is improved by the things done by the best of us. Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins are the best of us, and they’ve led us further and higher than we ever imagined we were likely to go.”

–Walter Cronkite, the legendary television journalist,

at the conclusion of his live broadcast coverage of the Apollo 11 moon landing

Today’s date is indelible. At least for those of us who care. My fear is that, these days, those of us who care are a distinct minority, a niche fandom like Trekkies or model train enthusiasts, just a bunch of aging white guys who indulge their inner 12-year-olds with a basement room in which they display their collections and imagine a world different than the way it is. If this day were a national holiday, as I’ve proposed before, maybe it would be different. Maybe people would remember and get excited and talk about the meaning of it all, and even become a little misty-eyed, as I do myself. But then… maybe not. Maybe a national holiday honoring the Apollo astronauts — and by extension all explorers, in my vision — would become just one more day for car dealers to hold a sale, and for families to grill some hot dogs without a second thought as to why they have this day off.

And then there’s that bit about “as long as Man survives” (forgive the outdated sexist usage in reference to the whole human species; it was 1969, after all). There are those who believe we humans don’t have much time left, that climate change and the bees dying and the oceans filling up with plastic will snuff out our collective flame by the end of the 21st century, if not a lot sooner. I’ll confess that on my more depressive days, I worry about that too, and I feel an absolutely crushing sense of futility. It’s on those days, more than any other, that I wish people would think about the Apollo program. That they would remember what human beings managed to do, and that they did it in a ridiculously short period of time, going from almost no idea of how to put people into space to putting them on another world in just slightly over one decade. Humanity can accomplish immense, glorious things if we put our minds to it. If we work together. If we restrain and channel our destructive impulses toward better, nobler, common goals, for the good of everyone and not just for the shareholders. Human beings built the pyramids, not aliens. And human beings did go to the moon, using technology that wasn’t much more sophisticated than stone knives and bearskins (to borrow a famous line from an old episode of Star Trek). The conspiracy theorists and the casual doubters who think it was all fake… these people infuriate me. Not because they’re scoffing at something I’ve always been fascinated by and excited about, although that is plenty irksome. But because they’re disparaging the one truth I firmly believe about our miserable little ape selves: that we can achieve greatness. That we can solve the big problems. The thing is, though, we need to believe that we can do it. We need to have the optimism that there is a way and that we can find it. And we need to be willing to spend the damn money.

Will humanity solve — or at least adapt to — the multiple environmental crises that seem to be looming higher and higher over our heads? I don’t know. I really don’t. Will we someday return to the moon? I don’t know that either, although it seems more likely right now than it has for many years. Honestly, I don’t even know anymore whether we should go back there, or if we should devote our efforts to Mars or to asteroid mining or to figuring out how to build O’Neill colonies in deep space. All I know is that we shouldn’t give up on the big things. On the hard things. That’s the real meaning of Apollo 11, the message we should take away from those fuzzy old black-and-white images of Neil and Buzz shuffling and hopping through the dust of another world. The lesson that we ought to be pounding into every school kid’s head every single day: the triumph of technology … the strength of Man’s resolve and the persistence of his imagination…

We need that spirit right now. Now more than ever. I hope we can summon it soon.